Data Centers

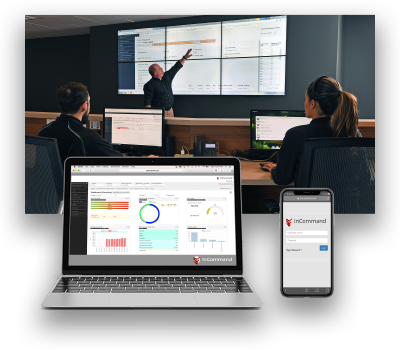

Serverfarm’s modern, award-winning global portfolio of data centers provides enterprises with critical IT infrastructure and capacity, along with a robust DMaaS solution. Our facilities were designed to meet our customers’ rapidly evolving requirements and are highly secure, reliable environments.